Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

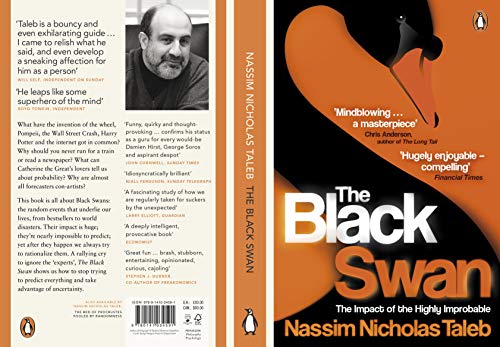

The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable [Nassim Nicholas Taleb] on desertcart.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable Review: A masterpiece of insightful information! - The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable by Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a thought-provoking and fascinating book that challenges readers to think differently about the role of randomness and uncertainty in our lives. The book offers a fresh perspective on the impact of rare, unpredictable events - or "black swans" - on our world, and provides readers with insights and strategies for navigating the complexities of a rapidly changing world. The book is divided into three parts. In the first part, Taleb introduces the concept of black swans and explains why they are so important. He argues that black swans are rare, high-impact events that are impossible to predict, yet have a profound effect on our world. He uses examples from history, economics, and other fields to illustrate the impact of black swans on our lives, and explains why we tend to underestimate their importance. In the second part of the book, Taleb explores the concept of "antifragility" - the idea that certain systems actually benefit from stress and volatility. He argues that many of our current systems, from financial markets to political systems, are too fragile and vulnerable to black swan events. He offers strategies for building antifragile systems that can better withstand the shocks and disruptions of the modern world. In the final part of the book, Taleb provides readers with practical advice for navigating a world full of black swans. He offers tips for managing risk, making decisions in uncertain situations, and living a more fulfilling and meaningful life. One of the strengths of the book is Taleb's engaging and accessible writing style. He has a talent for explaining complex ideas in clear and understandable language, making the book easy to follow and enjoyable to read. He also has a keen sense of humor, and his writing is often peppered with amusing anecdotes and observations. Another strength of the book is its relevance to our current world. The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect example of a black swan event, and Taleb's insights and strategies for managing uncertainty and risk are more relevant now than ever before. However, the book is not without its limitations. Taleb's writing style can be overly repetitive at times, and some readers may find certain sections of the book to be overly technical or dense. Additionally, while Taleb's insights and strategies are certainly valuable, they may not be applicable or accessible to everyone. Overall, The Black Swan is a thought-provoking and engaging book that challenges readers to think differently about the role of randomness and uncertainty in our lives. The book offers valuable insights and strategies for navigating a rapidly changing world, and is sure to be of interest to anyone looking to gain a deeper understanding of the complex systems that shape our world. Review: A Book That Changed My Life - The polemicist Simon Foucher warned that, “we are dogma-prone from our mother’s wombs.” Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s philosophical work, The Black Swan, is truly a masterpiece that addresses this problem. At one point in the book, Taleb asserts that “the ultimate test of whether you like an author is if you’ve reread him”. Considering the fact that I’ve now read this book twice, it’s fair to say that I greatly admire Taleb’s work. Now on to the review. *** In “Part 1″, there is an interesting anecdote, that sets the tone for the rest of the book, about Umberto Eco’s library. Eco is a highly respected semiotician, essayist, philosopher, literary critic, and novelist. And he owns a library that reportedly contains over 30,000 books. He isn’t, however, known for being boastful about it. When guests come over to his house he usually gets one of two reactions. The vast majority of guests, according to Taleb, respond with something similar to the following “Wow! Signore professore dottore Eco, what a library you have! How many of these books have you read?” And then there are the people who get the point: “A large personal library is not an ego-boosting appendage, but a research tool.” The point of this story emphasizes a critical theme throughout the book, i.e., we overemphasize what we think we know and downplay how ignorant we really are. An antilibrary (representing things we don’t know) is more valuable to us than are the books we’ve already read (or things we already know). Early on we also learn that Taleb classifies himself as a skeptical empiricist. And, you may be wondering, what exactly is a skeptical empiricist? “Let us call an antischolar — someone who focuses on the unread books, and makes an attempt not to treat his knowledge as a treasure, or even a possession, or even a self-esteem enhancement device — a skeptical empiricist.” For further clarification, empiricism is a theory of knowledge, which asserts that knowledge can only be ascertained exclusively via sensory experience. And skepticism, it’s important to note, comes in many different varieties. Taleb traces his skepticism back to its roots in the Pyrrhonian tradition. However, he is also fond of “Sextus the (Alas) Empirical” (better known as Sextus Empiricus) and David Hume. Taleb, however, is not entirely devoted to promoting rampant philosophical skepticism. He simply wants to be “a practitioner whose principal aim is to not be a sucker in things that matter, period.” Largely, then, this book is about epistemology, also known as the study of human knowledge. What can we truly know? And what are the limits of human knowledge? I think Taleb focuses one of the fundamental problems of philosophy, which the German Philosopher, Immanuel Kant, also wrote extensively about (although from a different perspective), i.e., what are the limits of our reason? Kant realized that examining human reason is inherently problematic, namely because when humans try to examine metaphysical or even epistemological issues we can never do so outside the bounds of our own reasoning ability. We’re suckers, blinded to reality, because we are trapped in our own human minds! Throughout the book, Taleb picks on the great thinker of antiquity, Plato. Taleb, however, also gives the impression that he is quite fond of the great philosopher too, despite his shortcomings. What Taleb calls Platonicity is the obsessive focus on the pure and well-defined aspects of reality, while ignoring the messier parts and less tractable structure that exist in reality. Perhaps an example of Platonicity might help clear up this distinction. A Platonified economist, for example, thinks that he can accurately model something as complex as the macroeconomy. Using foolish assumptions, the Platonified economist tries to assume conditions of reality (that don’t really exist) in order to fit her model rather than accepting that reality is far messier than the model. One who is a Platonic thinker, then, could also be classified as a nerd. Nerds, according to Taleb, believe that what cannot be Platonized and formally studied doesn’t exist, or isn’t worth considering. One interesting example of Platonicity provided in the book pertains to breast milk. At one point in time, Platonified scientists believed that they had created a formula for a mother’s “milk” that was perfectly identical to a mother’s real milk. Alas, they could then manufacture this milk in a laboratory and make financial gains from it! Despite what appeared to be an identical chemical composition, there was empirical evidence showing increases in various cancers and other health problems in children who drank this fake-milk. Was this a coincidence? Perhaps. But it also could be that the Platonified scientific formula for milk was missing some crucial element of the milk that we cannot see! Platoncitity can further be generalized as follows, “it is our tendency to mistake the map for the territory, to focus on well and pure defined “forms,” whether objects, like triangles, or social notions, like utopias (societies built according to some blueprint of what “makes sense”), even nationalities. “ In other words, a Platonified nerd is someone who visits New York City, but has with a map of San Francisco with them, and yet still thinks that their incorrect map will somehow help them. Taleb believes that we have a built-in tendency to trust our maps, even when they’re for the wrong location. Furthermore, we fail to realize that no map is often better than the wrong map. The trouble is, according to Taleb, that we encourage nerd knowledge over other forms of knowledge, especially in academia. Nerds focus on what fits in the box, even if the most important things in life fall outside the box. The nerd simply neglects the antilibrary. At one point in history it was considered “knowledge” that all swans are white. This was stated as a scientific fact because no black swans had ever been observed. However, this line of reasoning presents an interesting philosophical problem, i.e., “The Problem of Induction“. And the great philosopher, David Hume, wrote in great detail about this problem, although he wasn’t the first to do so. In order to further understand this problem let’s consider the following classic inference that led to the problem: All swans we have seen are white, and therefore all swans are white. The problem is that even the observation of a billion white swans does not make that statement unequivocally true. This is because black swans may exist, we just haven’t observed one yet. We have obviously since discovered that black swans do indeed exist. What can we learn here? An over reliance on our observations can lead us astray. Still confused? Then, let’s consider what we can we learn from a turkey, which hopefully provides further clarification. The uberphilsopher Bertrand Russell illustrated this turkey example quite well. Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race “looking out for its best interests,” as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving it will incur a revision of belief. Taleb, then, states, “The turkey problem can be generalized to any situation where the same hand that feeds you can be the one that wrings your neck.” Probably the most important point to note from the turkey is that our perceived knowledge from learning backwards may not just be worthless, but rather, it may actually be creating negative value by blinding us to future events with dire consequences. As such, it’s certainly important to note that a series of corroborative facts is not necessarily evidence. But where does that leave us in terms of how we can know things? Well, Taleb further argues that we can know things that are wrong, but not necessarily correct (think Karl Popper’s falsifiability). This he calls negative empiricism. The sight of one black swan, then, can certify that not all swans are white, but the observation of a trillion white swans doesn’t give us any certifiable claims. Strangely, however, we humans have a tendency to ignore the possibility of silent evidence and look to confirm our theories, rather than challenge them. One of the central tenets of the book is the distinction between “Mediocristan” and “Extremistan”, which are terms for different types of domains.. When you’re dealing with a domain that’s in Mediocristan, then your data will fit a Gaussian distribution (a bell curve). In Extremistan, however, you’re not dealing with data that is normally distributed. A single observation in Extremistan can have an incredible impact on the total. Think of the following example. If we took the average height of a million humans and then, say, added the tallest person in the world to the sample, the average wouldn’t be affected in a significant way. Height is normally distributed. Now imagine we did the same thing with wealth. Adding the richest person in the world to a sample of a million people would greatly affect the average. The distribution of height, then, falls within the domain of Mediocristan and things like wealth in Extremistan. One of Taleb’s main points is that we often try to use the model that works in Mediocristan in Extremistan. Taleb states, however, that almost all social matters belong to Extremistan and that the casino is the only human venture where probabilities are known and almost computable. But even casinos aren’t immune to Extremistan — think about it. Another interesting concept from the book is the “toxicity of knowledge.” Too much information can be toxic especially when it inflates the confidence in an “expert” prediction. More information is not always better; more is sometimes better, but not always. And we often blindly listen to experts in fields where there can be no experts. If you follow Taleb’s argument, then reading the newspaper may actually decrease, rather than increase, your knowledge of the world. The Black Swan, however, will not only increase your understanding of the world, but it will make you wiser as well. For that reason, I can assure you that I will be rereading this book yet again at some point in the future.

| Best Sellers Rank | #1,145,798 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #229 in Business & Money (Books) #8,696 in Women's Biographies #23,375 in Psychology & Counseling |

| Book 2 of 5 | Incerto |

| Customer Reviews | 4.4 4.4 out of 5 stars (8,005) |

| Dimensions | 1.2 x 5 x 7.7 inches |

| Edition | Re-issue |

| ISBN-10 | 0141034599 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0141034591 |

| Item Weight | 12.3 ounces |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 480 pages |

| Publication date | January 1, 2008 |

| Publisher | Penguin |

B**N

A masterpiece of insightful information!

The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable by Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a thought-provoking and fascinating book that challenges readers to think differently about the role of randomness and uncertainty in our lives. The book offers a fresh perspective on the impact of rare, unpredictable events - or "black swans" - on our world, and provides readers with insights and strategies for navigating the complexities of a rapidly changing world. The book is divided into three parts. In the first part, Taleb introduces the concept of black swans and explains why they are so important. He argues that black swans are rare, high-impact events that are impossible to predict, yet have a profound effect on our world. He uses examples from history, economics, and other fields to illustrate the impact of black swans on our lives, and explains why we tend to underestimate their importance. In the second part of the book, Taleb explores the concept of "antifragility" - the idea that certain systems actually benefit from stress and volatility. He argues that many of our current systems, from financial markets to political systems, are too fragile and vulnerable to black swan events. He offers strategies for building antifragile systems that can better withstand the shocks and disruptions of the modern world. In the final part of the book, Taleb provides readers with practical advice for navigating a world full of black swans. He offers tips for managing risk, making decisions in uncertain situations, and living a more fulfilling and meaningful life. One of the strengths of the book is Taleb's engaging and accessible writing style. He has a talent for explaining complex ideas in clear and understandable language, making the book easy to follow and enjoyable to read. He also has a keen sense of humor, and his writing is often peppered with amusing anecdotes and observations. Another strength of the book is its relevance to our current world. The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect example of a black swan event, and Taleb's insights and strategies for managing uncertainty and risk are more relevant now than ever before. However, the book is not without its limitations. Taleb's writing style can be overly repetitive at times, and some readers may find certain sections of the book to be overly technical or dense. Additionally, while Taleb's insights and strategies are certainly valuable, they may not be applicable or accessible to everyone. Overall, The Black Swan is a thought-provoking and engaging book that challenges readers to think differently about the role of randomness and uncertainty in our lives. The book offers valuable insights and strategies for navigating a rapidly changing world, and is sure to be of interest to anyone looking to gain a deeper understanding of the complex systems that shape our world.

G**R

A Book That Changed My Life

The polemicist Simon Foucher warned that, “we are dogma-prone from our mother’s wombs.” Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s philosophical work, The Black Swan, is truly a masterpiece that addresses this problem. At one point in the book, Taleb asserts that “the ultimate test of whether you like an author is if you’ve reread him”. Considering the fact that I’ve now read this book twice, it’s fair to say that I greatly admire Taleb’s work. Now on to the review. *** In “Part 1″, there is an interesting anecdote, that sets the tone for the rest of the book, about Umberto Eco’s library. Eco is a highly respected semiotician, essayist, philosopher, literary critic, and novelist. And he owns a library that reportedly contains over 30,000 books. He isn’t, however, known for being boastful about it. When guests come over to his house he usually gets one of two reactions. The vast majority of guests, according to Taleb, respond with something similar to the following “Wow! Signore professore dottore Eco, what a library you have! How many of these books have you read?” And then there are the people who get the point: “A large personal library is not an ego-boosting appendage, but a research tool.” The point of this story emphasizes a critical theme throughout the book, i.e., we overemphasize what we think we know and downplay how ignorant we really are. An antilibrary (representing things we don’t know) is more valuable to us than are the books we’ve already read (or things we already know). Early on we also learn that Taleb classifies himself as a skeptical empiricist. And, you may be wondering, what exactly is a skeptical empiricist? “Let us call an antischolar — someone who focuses on the unread books, and makes an attempt not to treat his knowledge as a treasure, or even a possession, or even a self-esteem enhancement device — a skeptical empiricist.” For further clarification, empiricism is a theory of knowledge, which asserts that knowledge can only be ascertained exclusively via sensory experience. And skepticism, it’s important to note, comes in many different varieties. Taleb traces his skepticism back to its roots in the Pyrrhonian tradition. However, he is also fond of “Sextus the (Alas) Empirical” (better known as Sextus Empiricus) and David Hume. Taleb, however, is not entirely devoted to promoting rampant philosophical skepticism. He simply wants to be “a practitioner whose principal aim is to not be a sucker in things that matter, period.” Largely, then, this book is about epistemology, also known as the study of human knowledge. What can we truly know? And what are the limits of human knowledge? I think Taleb focuses one of the fundamental problems of philosophy, which the German Philosopher, Immanuel Kant, also wrote extensively about (although from a different perspective), i.e., what are the limits of our reason? Kant realized that examining human reason is inherently problematic, namely because when humans try to examine metaphysical or even epistemological issues we can never do so outside the bounds of our own reasoning ability. We’re suckers, blinded to reality, because we are trapped in our own human minds! Throughout the book, Taleb picks on the great thinker of antiquity, Plato. Taleb, however, also gives the impression that he is quite fond of the great philosopher too, despite his shortcomings. What Taleb calls Platonicity is the obsessive focus on the pure and well-defined aspects of reality, while ignoring the messier parts and less tractable structure that exist in reality. Perhaps an example of Platonicity might help clear up this distinction. A Platonified economist, for example, thinks that he can accurately model something as complex as the macroeconomy. Using foolish assumptions, the Platonified economist tries to assume conditions of reality (that don’t really exist) in order to fit her model rather than accepting that reality is far messier than the model. One who is a Platonic thinker, then, could also be classified as a nerd. Nerds, according to Taleb, believe that what cannot be Platonized and formally studied doesn’t exist, or isn’t worth considering. One interesting example of Platonicity provided in the book pertains to breast milk. At one point in time, Platonified scientists believed that they had created a formula for a mother’s “milk” that was perfectly identical to a mother’s real milk. Alas, they could then manufacture this milk in a laboratory and make financial gains from it! Despite what appeared to be an identical chemical composition, there was empirical evidence showing increases in various cancers and other health problems in children who drank this fake-milk. Was this a coincidence? Perhaps. But it also could be that the Platonified scientific formula for milk was missing some crucial element of the milk that we cannot see! Platoncitity can further be generalized as follows, “it is our tendency to mistake the map for the territory, to focus on well and pure defined “forms,” whether objects, like triangles, or social notions, like utopias (societies built according to some blueprint of what “makes sense”), even nationalities. “ In other words, a Platonified nerd is someone who visits New York City, but has with a map of San Francisco with them, and yet still thinks that their incorrect map will somehow help them. Taleb believes that we have a built-in tendency to trust our maps, even when they’re for the wrong location. Furthermore, we fail to realize that no map is often better than the wrong map. The trouble is, according to Taleb, that we encourage nerd knowledge over other forms of knowledge, especially in academia. Nerds focus on what fits in the box, even if the most important things in life fall outside the box. The nerd simply neglects the antilibrary. At one point in history it was considered “knowledge” that all swans are white. This was stated as a scientific fact because no black swans had ever been observed. However, this line of reasoning presents an interesting philosophical problem, i.e., “The Problem of Induction“. And the great philosopher, David Hume, wrote in great detail about this problem, although he wasn’t the first to do so. In order to further understand this problem let’s consider the following classic inference that led to the problem: All swans we have seen are white, and therefore all swans are white. The problem is that even the observation of a billion white swans does not make that statement unequivocally true. This is because black swans may exist, we just haven’t observed one yet. We have obviously since discovered that black swans do indeed exist. What can we learn here? An over reliance on our observations can lead us astray. Still confused? Then, let’s consider what we can we learn from a turkey, which hopefully provides further clarification. The uberphilsopher Bertrand Russell illustrated this turkey example quite well. Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race “looking out for its best interests,” as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving it will incur a revision of belief. Taleb, then, states, “The turkey problem can be generalized to any situation where the same hand that feeds you can be the one that wrings your neck.” Probably the most important point to note from the turkey is that our perceived knowledge from learning backwards may not just be worthless, but rather, it may actually be creating negative value by blinding us to future events with dire consequences. As such, it’s certainly important to note that a series of corroborative facts is not necessarily evidence. But where does that leave us in terms of how we can know things? Well, Taleb further argues that we can know things that are wrong, but not necessarily correct (think Karl Popper’s falsifiability). This he calls negative empiricism. The sight of one black swan, then, can certify that not all swans are white, but the observation of a trillion white swans doesn’t give us any certifiable claims. Strangely, however, we humans have a tendency to ignore the possibility of silent evidence and look to confirm our theories, rather than challenge them. One of the central tenets of the book is the distinction between “Mediocristan” and “Extremistan”, which are terms for different types of domains.. When you’re dealing with a domain that’s in Mediocristan, then your data will fit a Gaussian distribution (a bell curve). In Extremistan, however, you’re not dealing with data that is normally distributed. A single observation in Extremistan can have an incredible impact on the total. Think of the following example. If we took the average height of a million humans and then, say, added the tallest person in the world to the sample, the average wouldn’t be affected in a significant way. Height is normally distributed. Now imagine we did the same thing with wealth. Adding the richest person in the world to a sample of a million people would greatly affect the average. The distribution of height, then, falls within the domain of Mediocristan and things like wealth in Extremistan. One of Taleb’s main points is that we often try to use the model that works in Mediocristan in Extremistan. Taleb states, however, that almost all social matters belong to Extremistan and that the casino is the only human venture where probabilities are known and almost computable. But even casinos aren’t immune to Extremistan — think about it. Another interesting concept from the book is the “toxicity of knowledge.” Too much information can be toxic especially when it inflates the confidence in an “expert” prediction. More information is not always better; more is sometimes better, but not always. And we often blindly listen to experts in fields where there can be no experts. If you follow Taleb’s argument, then reading the newspaper may actually decrease, rather than increase, your knowledge of the world. The Black Swan, however, will not only increase your understanding of the world, but it will make you wiser as well. For that reason, I can assure you that I will be rereading this book yet again at some point in the future.

A**E

Not an easy read but worth your time. Must read for anyone working in the fields of economy/business. Eye opening. As per usual with Taleb, it’s packed with information and academic back but that’s doesn’t mean I did not laughed out loud from time to time. Great scientist, great author!

S**N

Book came on time and in perfect condition. Great seller and highly recommend!

A**R

Good read. Makes us think about alternatives and chances.

T**Y

good book

E**L

I am an Economist , needless to say i felt attacked a bit reading the book (if you read it you will get it), however you see that the point he is trying to make is very very powerful, so managing that he goes overboard and exaggerate on some things (various actually) will make you understand him more and understand his point of the power of the unknown which do seems to be forgotten about as if everything was predictable and expected, his style of writing is interesting, funny (sometimes) and clever, would recommend is an excellent book from NNT, its like opening a cookie jar who has an excellent cookie but slaps you a bit before you get it.

Trustpilot

3 days ago

2 weeks ago